Some time ago, I had a discussion with a friend and fellow academic about the OSR — the Old School Revival, Renaissance, or possibly Rules. Coming at this from an indie games perspective, he said he had never encountered any sort of theory behind the OSR, any attempt to provide an explanatory framework for what the OSR is about and why. I found that to be an interesting — and challenging — statement, and it seemed to me that there was room for a discussion about that subject. Since the OSR has been around for almost 20 years, it seemed to be worthwhile to dig deeper into this.

I probably ought to start by saying that the OSR has many manifestations, and they are not all in agreement or alignment with each other. Some of those manifestations include (but are not limited to):

- Playing older editions or versions of D&D, e.g. OD&D, B/X, AD&D 1st or 2nd Edition

- Playing retro-clones of older editions or versions of D&D, e.g. Labyrinth Lord, Old School Essentials, Swords & Wizardry, Basic Fantasy Roleplaying Game

- Playing games associated with older editions or versions of D&D, e.g. Empire of the Petal Throne, Metamorphosis: Alpha, Gamma World, Boot Hill, Top Secret (all of these are TSR products)

- Playing games written in reaction to D&D, e.g. Tunnels & Trolls, Chivalry & Sorcery, Arduin Grimoire, Runequest, Traveller

- Games written from a more contemporary or narrative-informed perspective, but still informed by an old school perspective, e.g. The Black Hack, Into the Odd, Knave, Maze Rats

It is safe to say that these last two categories of manifestations represent the “hinterland” of the OSR, in that there are fans of all of the games mentioned who would not think of them as being primarily about their relationship to D&D. So we can use D&D, specifically older editions of D&D, as a reference point for the OSR, but probably not as a defining element. More narratively-informed games also have their own ideas about how to play (see below); some of this contributes to the more-recently named “new school” or “NuSR” play style and game design.

But the OSR is more than a preference for playing older versions of D&D or related games. It also involves the subject of play:

- Original settings and worlds, created by players, e.g. Hellsgate, Gorree, The Ryth Chronicle

- Published adventures, some of which were based on tournament modules written for use at conventions, e.g. Keep on the Borderlands, Against the Giants, White Plume Mountain

- Published worlds and settings, e.g. First Fantasy Campaign [Blackmoor], (The World of) Greyhawk, Forgotten Realms, Athas, City-State of the Invincible Overlord and Wilderlands of High Fantasy, Irilian

- Material for games which has been adapted to more OSR-compatible play, e.g. Dark Sun B/X

The OSR also involves how to play. This deserves its own entire series of posts, but we will start with some attempts to describe or codify differences in OSR play from other styles of play:

- A Quick Primer for Old School Gaming by Matt Finch The Quick Primer describes differences between the then-emergent Old School playstyle and 3.0/3.5 D&D dominant playstyle

- Philotomy’s Musings, by Jason Cone. This is a comprehensive look at a mindset and perspective change to assist in playing Original D&D

- Principia Apocrypha, by Ben Milton, Steven Lumpkin, and David Perry. This is an Old School primer “in the form of a collection of Apocalypse World-style GM and Player Principles.”

- The Gygax 75 Challenge, by Ray Otus. This draws on an article written by Gary Gygax for Europa 6-8, in 1975, to provide a framework for building your own world.

This is by no means a complete list. There is a considerable amount of material on the internet, specifically on blogs, about what constitutes “Old School” game play, and how to go about it. What should be clear from all of this is that the OSR might be conceived of as a Venn diagramme, with games, rules, and what and how to play as an overlapping set of circles of interest and validity.

One particular criticism which has been made is to suggest that the apparent incoherence of “Old School” writing and perspectives, as demonstrated by the vast array of writers and seeming contradictions between them, means that it would be impossible to theorize in any meaningful way about the OSR. While I understand this criticism, I would note that an absence of evidence is not evidence of absence. I would also note that the degree to which it is possible to describe the OSR, and OSR types of games, suggests that it is possible to theorize about the OSR, we just need to investigate this further.

Since this is an introductory post, I am very interested in constructive commentary.

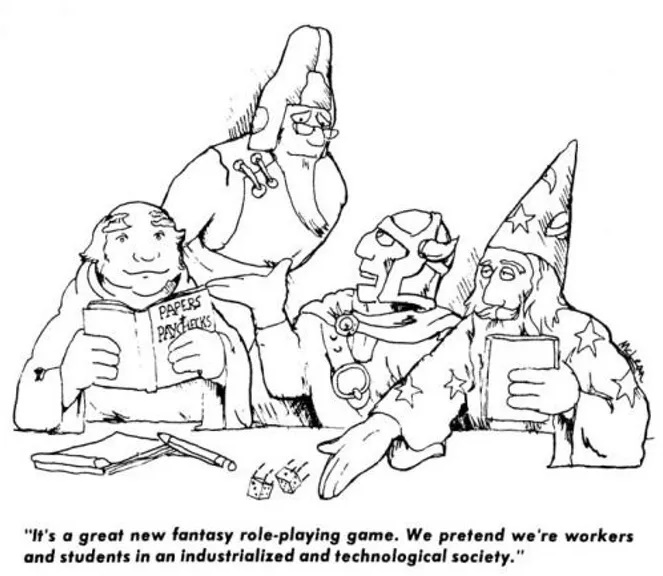

[Cartoon by Will McLean, originally appearing in the AD&D Dungeon Masters Guide, 1979-1980]

Hi Victor, My rpg friends and I have been playing FGU’s Bushido for decades, since it came out. Nothing has come along that quite captures its peculiar take on role playing in a fantasy oriental world. As far as reason for using the original rules it is because, for well known reasons there has been no newer version.

Oops , got that wrong, we use second edition …

No worries – I must admit, I have found Bushido to be an endlessly fascinating game.

Re: “One particular criticism which has been made is to suggest that the apparent incoherence of “Old School” writing and perspectives, as demonstrated by the vast array of writers and seeming contradictions between them, means that it would be impossible to theorize in any meaningful way about the OSR.”

1975-77 were sort of a Cambrian Explosion of RPGs. There was a profusion of D&D variants but also a profusion of RPGs in general. A blanket term like old-school roleplaying is bound to be vague. It would be presumptuous of anyone now to try to impose conformity of thought on that era from this distance.

I don’t think you’re chasing rainbows, but I do think any effort to define old-school gaming has got to face its diversity squarely.

One of the more fascinating aspects of the whole thing to me is the number of people drawn to old-school gaming who are too young to have experienced any of it first-hand. Their notions of what constitutes old-school may be more illuminating than many a grognard’s.

“[A]ny effort to define old-school gaming has got to face its diversity squarely.” Absolutely. I’m going about this cautiously, for precisely that reason.

“It would be presumptuous of anyone now to try to impose conformity of thought on that era from this distance.” Totally true. But that doesn’t mean we shouldn’t attempt to explore what makes the OSR different, to find those elements that can be used to distinguish it from more modern games.